Operational Planning

An operational plan is a schedule of related operational processes, that constitute a body of scheduled work with defined deliverable(s). A plan normally contains one or more process resource flows, one for each deliverable. It can also contain the reciprocal agreements expected for agents involved in the flows. Plans can be large or small, for example daily planning for work on a production line or dairy, up to a season's plan for an annual harvest.

See also Flows in motion: Planning in the Diagram Explanations, the Recipes page, and the Planning examples.

Coordinating work

Plans are used for understanding and coordinating what needs to happen for specific outputs. The size and complexity of a plan is up to the people who are planning and coordinating the work.

A plan can cover more than one organization, if the processes are tightly coordinated with pre-agreed rules, for example sub-organizations of a main organization, or a collaborative supply chain. If not, or if the agents prefer to manage their plans themselves, then requirements from one agent could become deliverables for another agent's plan. Different batch sizes could trigger a new plan for inputs to the main deliverable too, but doesn't have to, it just implies another output of the plan. But all of this does not affect the vocabulary or model.

Some examples:

-

A communications group creates articles for a larger group. The communications group needs some of their articles to be translated into various languages, by another group within the larger group. Both the creation of an article and its translation could be part of the same plan.

-

An organization decides to mount a campaign for some objective. There might be many different deliverables: a fundraising website, some brochures, some events, etc. All of these can be part of the same plan for easier coordination. For example, a campaign logo could be used in all of these separate outputs.

-

An organization gets an order for some things they produce. They can create a plan to produce to that order, including all line items. Or they can gather all the orders for a time period for an item and produce to that as a larger plan.

-

An organization produces a standard batch size to stock, in anticipation of future orders.

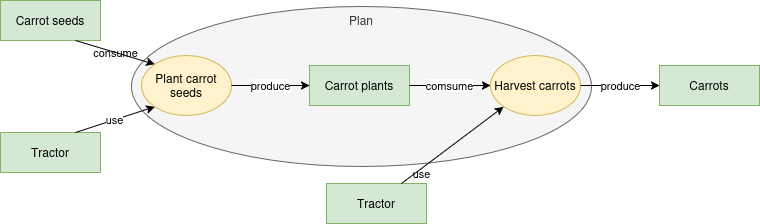

Processes nested in a Plan

When processes are "nested", it is not random, nor based on a taxonomy. It is based on what processes are actually part of the plan. Not all the inputs and outputs of nested processes are considered inputs and outputs of the plan, since some are both produced and consumed within the plan. In the following simplified example, the carrot plants start and end inside the plan, and so are not thought of as an input or output of the plan. So plans can have implied relationships to each other through resource flows just like processes.

There are some common situations for nested processes that will not be as simple as the above diagram. These include:

- Action makes a difference. When a piece of equipment or tool is "used", it is not gone at the end of the nesting process. But if it is managed as a time-based resource with a calendar, some calendar duration is in fact consumed. Or if a citable resource is created and then cited inside, it is also still there at the end of the plan.

- Batch or lot size makes a difference. Suppose you have a requirement for 5 of some assembled item, and 4 of some input component are needed to make each item, 20 components in all. But the minimum batch size for the component is 100. Then 80 of the components will be left in inventory at the end of the plan.

Thinking about supply and demand

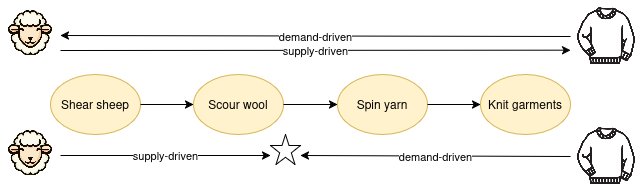

Longer flows can be supply-driven, demand-driven, or both, meeting somewhere in the middle. This matters when defining recipes.

Most manufacturing is demand-driven; many agriculture settings are more supply-driven. But those are not rules, and each situation should be analyzed.

For example in the simplified textile supply chain below, at the top you see totally demand-driven and totally supply-driven. For example, demand-driven starts with how many of the garments does the agent want to produce this season, and uses the recipe flows to know they need to start with certain quantities of wool. The supply-driven starts with what wool is produced on the farms and calculates how many of what garments can be produced in the season.

On the bottom is a scenario that starts demand-driven, but when they see they can get extra sheep wool from the farms, they decide to purchase as much as they can because some years it is hard to get enough. They send it through the scouring process because saving greasy wool is not so pleasant.

Planning from recipe

A plan can be generated from one or more recipes, or created without recipes. For repeatable processing, it makes a lot of sense to automate planning from recipes. Otherwise, plans can be entered directly.

If there are Recipe classes, the planning uses only Recipe Processes that are defined in a Recipe. Or they can be generated directly from one or more Recipe Processes. In either case, they will find predescessor/successor Recipe Processes as needed.

Back-scheduling a plan from a Resource Specification or Recipe: Start with a resource specification, or the primary output of a recipe, and a due date, find a recipe process with that output, generate the plan from the end item to its inputs, to the outputs leading the inputs, to their inputs, etc. This is called a "demand explosion", and is probably the most common method.

Forward-scheduling from a Resource Specification or Recipe: Start with the inputs with no predecessors and a start date, generate the plan from the inputs to their outputs, to the inputs that want the outputs, etc..

Forward-scheduling from a Resource: Start with an Economic Resource, and generate the plan based on the recipe of its Resource Specification. Examples:

- Translation: start with a source document

- Auto repair: start with an auto that needs repair.

Generating a plan involves scaling the recipe according to the demanded quantity or supplied quantity, depending on the direction. Usually recipes are defined with the smallest reasonable batch quantities.

Software that generates plans from recipes can actually be pretty smart. It can check for what is currently in inventory, as well as what is already planned to be consumed or produced in other plans on what dates, and schedule only what is needed needed. It can report what inputs there aren't enough of and can either generate a plan from a recipe that makes those or schedule trading for those components or ingredients. The scaling calculations can be made as complex as necessary, for example usually the resource quantities are just multiplied out, but the time duration of a process might be less than a straight multiplication. If there are offers for resources, the planning can take that into account and insert agents appropriately.

In addition, often plans are tweaked after generation from a recipe, depending on how firm and exact the recipe is. A manufacturing recipe might be more exact than a recipe for a more general business process. For these reasons, a plan is decoupled from the recipe that generated it in the vocabulary. It maintains only the references to the resource and process specifications that were supplied from the recipe.

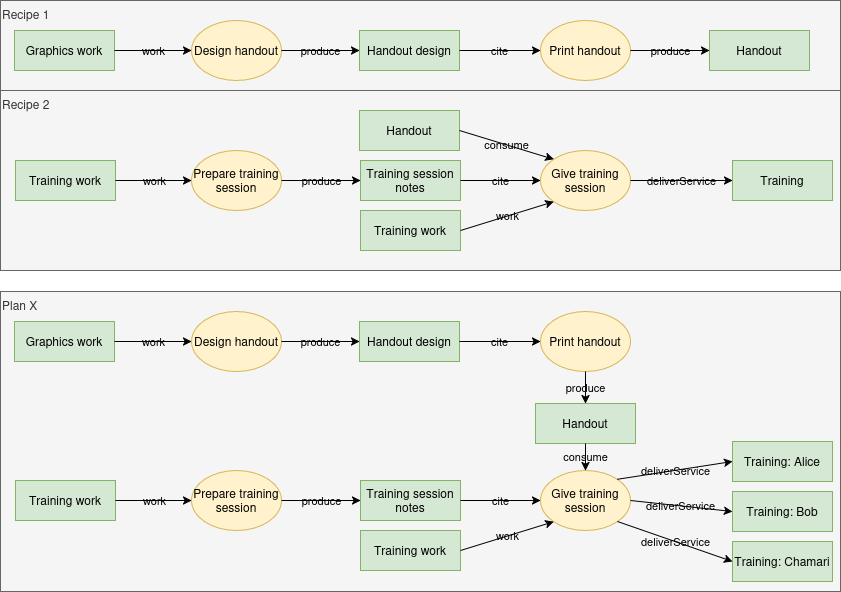

Note that a plan can include sets of flows from more than one recipe. For example, below is a simplified diagram of a plan that uses two recipes. In this example, the flows are related. But sometimes plans contain multiple sets of processes, each from a different recipe, and each set of processes delivers a different resource. For example, a plan for a marketing campaign might include producing pamphlets, making a website, conducting a few events, each of which is a separate recipe with a set of connected processes.